No one cared about Multi Armed Bandit’s tech

In mid-2017, inspired by the book “Bandit Algorithms for Website Optimization” by John Myles White, I decided to implement a service allowing Globo.com products to use Multi Armed Bandit algorithms to optimize their usability.

The algorithms explained in the book are relatively simple. Epsilon-Greedy, Softmax, and UCB are simple statistical calculations that do not require a great processing power or historical storage. So technically it would be possible to aggregate the necessary information in the memory of the service itself, avoiding any IO, enabling the service to have very low latency.

To keep everything in memory and maintain consistency, a first alternative would be to handle all requests on a single server scaled vertically. We know how dangerous this is in terms of resilience. So, a second alternative would be to have multiple servers behind a load balancer, reducing the consistency of aggregations slightly, and relying on the fact that the site’s huge audience will bring the numbers recorded on each server closer together.

These two possible alternatives would also require that the servers be pre-scaled for the most critical peak moments of the portal. At dawn, for example, when there were very few accesses, we would continue with the same cost as the periods of the most absurd traffic. Something we do not desire.

The ideal alternative would be to try to use concepts like autoscaling and multiple containers, which are already default decisions in the deployment of new services today. At Globo.com, we already had an internal PaaS called Tsuru, which is open source, and I have not seen anything better in any other company to this day.

However, for a service that is not stateless, the autoscaling process can be painful.

Imagine the situation where we have 20 pods in the air serving requests, all of them already have their aggregated numbers stabilized and generating the best results for each experiment. Then a peak time starts, new pods are allocated, and we go to 30 pods. At this peak moment, a very important moment for the site, 33% of requests no longer have the most optimized version in terms of results.

In other words, the regret metric we aim to minimize does not get reduced to the desired extent in the case of a stateful service with autoscaling.

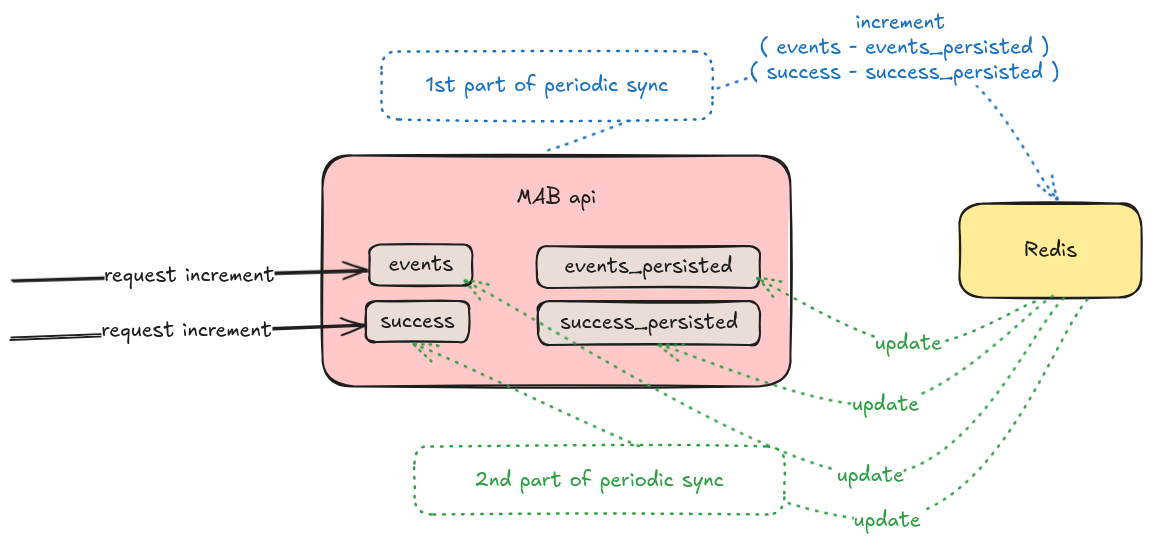

The solution found was to create a periodic sync of each service instance with a common Redis. So, in addition to storing in the service’s memory the total number of events and the total number of successes for each experiment, we also started storing in the service’s memory the values found in the common memory represented by Redis. In this sync, the service increment Redis keys with the difference between the current state and what was in the last sync, updating the common memory. After this, the sync gets those keys from Redis updating its internal states. Always using atomic variables.

With this, when a new pod is created due to auto scaling, we start it reading those keys from redis, so it is born with the necessary aggregated data for a more optimal choice that reduces regret for each experiment.

It’s been over seven years and I know that Multi Armed Bandit is still used at Globo.com because it is possible to observe the service requests when accessing the Portal. However, I believe that the service may have been completely modified by now. It was initially created in single day during a hackday, written using Scala and Finagle, and after that was used for various optimizations at Globo.com, from choosing a photo to selecting the best position to place advertising.

When I presented it at hackday, I wanted to emphasize this technological solution involving low latency and scalable eventual consistency for its operation as the interesting part of the project. In my mind, the calculations were so simple that they didn’t even deserve much attention because it is very simple to replicate them either all in memory, or by spending latency using IO massively.

However, the technological aspect of this solution did not receive the attention that I thought it deserved. What most sparked interest, obviously, were the expectations of use for improving usability that such a project could bring to users and all its possibilities. In other words, no one cares about the technological solution explicitly, but implicitly, they were crucial for maximizing results, minimizing regret in periods of auto scaling, reducing costs, and reducing latency.

I like to believe, in the depths of my being, that without this technological solution, the project would not have been used by so many products with as much success as it was. But is that really true?